The '27 Victory Of Vitaphone

Revisiting Show Biz History With The Jazz Singer

Another of those landmarks too famous for its own good, The Jazz Singer is met at last on even ground that is Warners' Blu-Ray, a fairest shake for the talking pioneer since Vitaphone discs first spun to nitrate accompany. Revivals of The Jazz Singer since 1927 tended toward re-record of sound, then re-record from re-records, losing for generations fresh impact the revolutionary process had. Accounts from the time confirm that when it worked, Vitaphone had no peer for clarity and amplification. There were snafus, plenty, but audiences understood what these shows could sound like, so were patient as kinks ironed out. All knew a future was upon them, talkies a given to come, whatever might become of silent traditions. The Jazz Singerwould not wipe out an era single-hand; it took a couple more years and many all-talkies to fully achieve that, but ease of reference permitted The Jazz Singer to define transition as overnight, an expediency more manageable than truth. What I note from seeing and hearing The Jazz Singer in High-Def is what an enjoyable experience it now is, memories of 16mm and TV broadcasts purified by cleansing wave that is digital.

There continues to be discussion, ninety years going, on just what electrified crowds at 1927 runs and inspired their coming back. There had been Al Jolson on talking screens a year back in the single reel A Plantation Act, which played as Vitaphone partner to full-length The Better 'Ole, a Sydney Chaplin comedy with music overlay and no dialogue per se. A Plantation Act was Jolson addressing us with three songs, limited patter, then three bows as he withdrew. This priceless short went missing for many decades until WB found the picture portion and a busted-to-pieces Vitaphone record that was miraculously reassembled. So why didn't A Plantation Act create a 1926 sensation? From myriad of reasons, I'd submit one, that being Plantation Al directing his tunes to unseen viewers (us), while The Jazz Singer had him performing songs before an on-screen audience. Their response is enthusiastic, and more important, infectious. The nitery where grown-up "Jack Robin" first sings is filled and noisy. His songs tap into the excitement and we too are engaged, a first time, I'd propose, when shadow viewers could entice live ones to join their applause. Jolson later singing to his mother allows us to react with her, added energy coming of the emotion they and we invested. This had been a commonplace since film began, but never before with talking plus music. A new way of enjoying movies was born with these two at an upright piano, and a new day for intimacy shared with characters on a screen.

I've seen a lot of reference to what a bombastic over-actor Al Jolson was, but on evidence of The Jazz Singer, I don't buy it. The move from silence to sound affected him as it would a number of players, even though Jolson had no prior experience with the film medium. He certainly would have had plenty as a spectator, however, and must have somehow convinced himself that to talk in pictures was to turn switches full-on. As a voiceless participant in The Jazz Singer, however, Jolson stays on pitch with others of the cast and does not hog scenes. He underplays with Warner Oland (as his father) and makes moving their conflict. When he does speak, Jolson sells the personality and songs, which was, of course, what he was hired for. I realize much got out of hand later when Jolson felt his oats and overestimated a public's lust to see and hear him, and maybe it's my perception that misreads what to others would be a hoke performance in The Jazz Singer, so to scoffers I'd only say, watch it again, but please do so with the Blu-ray or a TCM broadcast in HD.

Earliest musicals caught beautifully the whiff of backstage life, never minding gritty truth where putting on shows. Most of

Hick towns and outliers could but dream of Al Jolson singing from screens. They'd wait, in some cases several years, for talk to be installed in rural houses. In a meantime there were follow-up Jolsons, at least one, The Singing Fool, a bigger hit than The Jazz Singer. Still, the latter had the legend, and whatever of Al's the old-timers saw, they'd invariably recall the experience as The Jazz Singer. It became a generic Jolson title just as

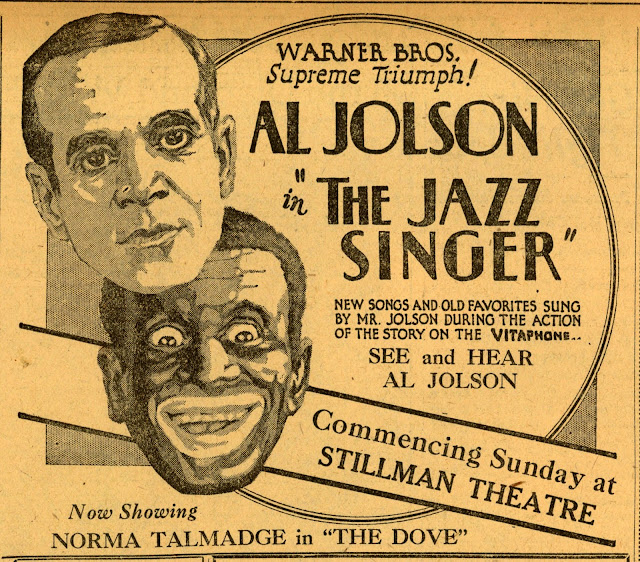

The Jazz Singer would henceforth be seen mostly in clips, but these were considerable, as each time WB congratulated itself for introducing sound, out would come Jolson kneeling to sing Mammy. The oft-seen highlight was enough to make many imagine they had seen The Jazz Singer in toto. Films out of rival companies nodded to WB's pioneering, The Jazz Singer cited for decades as the one that talked first. Television sale of Warners' pre-49 library made The Jazz Singer available to local stations, this following a theatrical window through Dominant Pictures for some of titles, including The Jazz Singer. There was fresh paper offered to showmen (the one-sheet at right), but so far, I've found no ads for an actual theatre run. Did any venue roll dice on The Jazz Singer in 1956-57? Revival houses steered wide of most things Jolson for the blackface wrinkle, plus fact he was distinctly un-cool except to ancients who'd stay home in front of their TV in any event. The Jazz Singer can be seen better than ever on Blu-ray, but by how many? All of its initial audience is gone or pushing 100 (I'm saying that a lot lately), so we who care can only imagine what impact was felt when Vitaphone saw Jolson performing on his knees for a public brought to theirs by 1927's modern miracle.

Comments

Post a Comment